6 Photographers on How They Shoot Rivers

Elk stampedes, drowned cameras, 4am wake-up calls, crazy drivers, the sensation of wading across greased bowling balls…these are some of the things photographers experience when they go out to shoot rivers that WRC is working to conserve.

Since the earliest days of conservation, art, and the people who make it, have moved us to protect wild places. The paintings of Thomas Moran and photographs of Carleton Watkins, for example, helped make Yellowstone and Yosemite national parks. Seeing a place—even through someone else's eyes—can inspire us to save it.

WRC works with some exceptional photographers who venture into remote corners of the West to capture the places you're helping us protect. Part of why they do it is their love of rivers, and because they believe in this work. Their photos play a significant role in inspiring others to support our efforts.

We asked six of these photographers—whose images you've likely seen—to share what it's like to photograph a WRC project. What surprised them? What challenged them? And what can they teach us about seeing rivers the way they do?

Their insights might just change the way you look at—and photograph—a river.

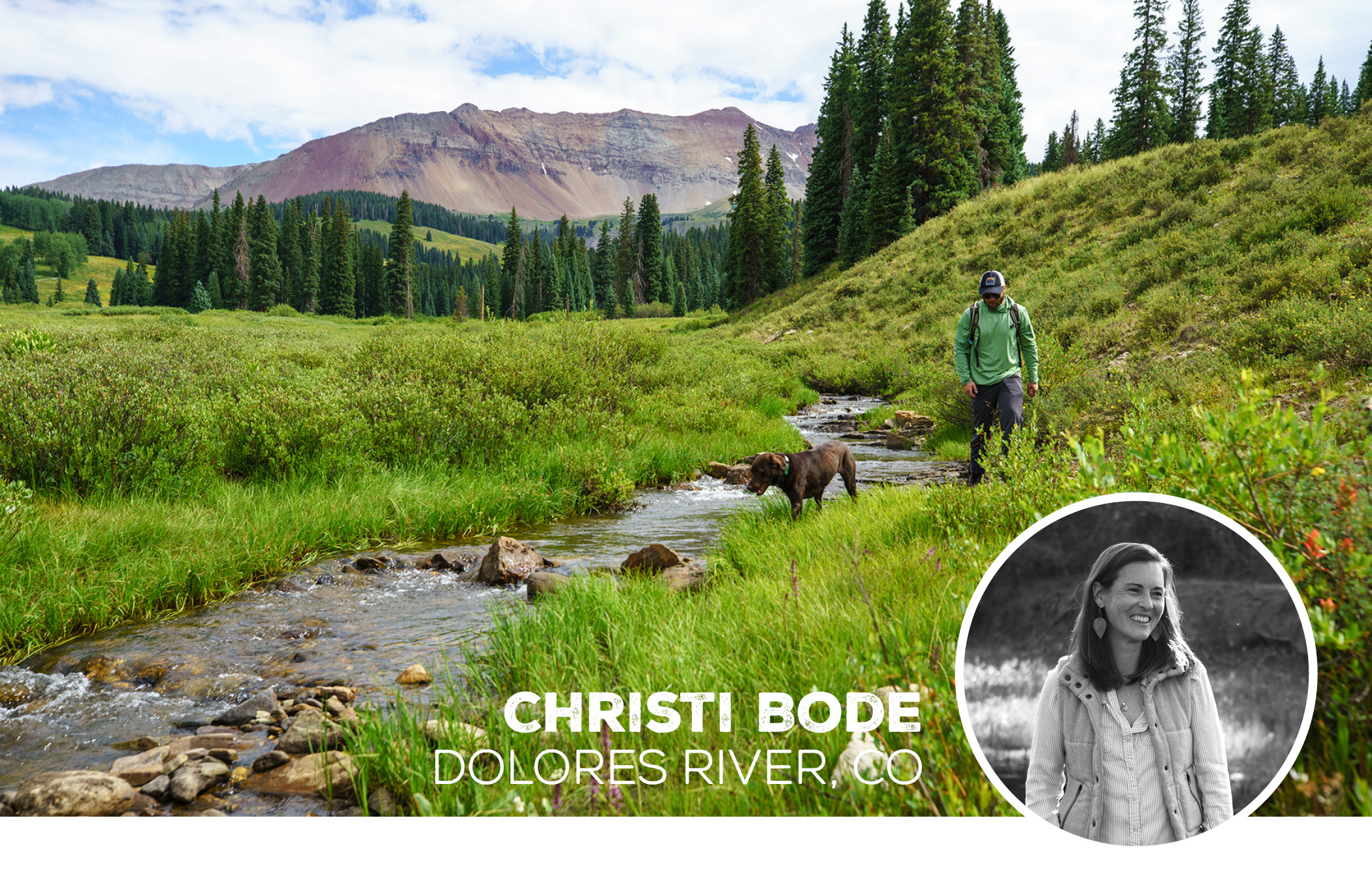

What was your favorite part about shooting the Dolores River?

What was your favorite part about shooting the Dolores River?

There's something about being at the headwaters of a major river system that's humbling and awe-inspiring. Fourteen-thousand-foot peaks. Young spruce-fir trees defining the ragged edge of the forest. Soft, trickling sounds of snow melt finding its way to a stream. Dunton Meadows is where the story of the Dolores River begins. This river means a lot to everyone and everything that depends on her—from the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and native strains of Colorado River cutthroat trout to boaters and other downstream users who seek these waters for refuge.

I'll take an outdoor office over a computer screen any day, but what's most special about photographing these places is being reminded how small I am, in the best way possible.

What challenges did you have during the shoot?

What is physically represented on a map or verbally communicated over the phone isn't always true to reality. It quickly became apparent that a "picnic along the stream" was not a shot I was going to get. It was more of a, "let's bring our bear mace because this riparian vegetation is so thick" kind of situation. I see challenges as adventures when it comes to these types of assignments. It's always good to have a backup plan, especially at higher elevations where weather and conditions change rapidly - minute to minute, day to day, year to year.

What are your top tips for photographing rivers?

1. Bring snacks. I can't emphasize this enough, especially if you're someone who goes from hungry to hangry in five minutes. Oftentimes, waiting for the light to seep in or the clouds to part can be a hurry up and wait situation. The closest store or gas station is 60-plus minutes away. I can't take a good photograph if I'm hangry, nor should your model have to endure hanger, so bring snacks to share.

2. Be flexible, because Mother Nature has plans of her own. I highly recommend planning to the extent that you can—triple check weather, sunrise and sunset times, public access points, etc. Sometimes, I have to forgo original plans because of wildfire smoke, sketchy road conditions or a moose that refuses to move (true story). The river will be there when the right time comes.

See more of Christi's work: moxiecranmedia.com and on Instagram at @christi_b.

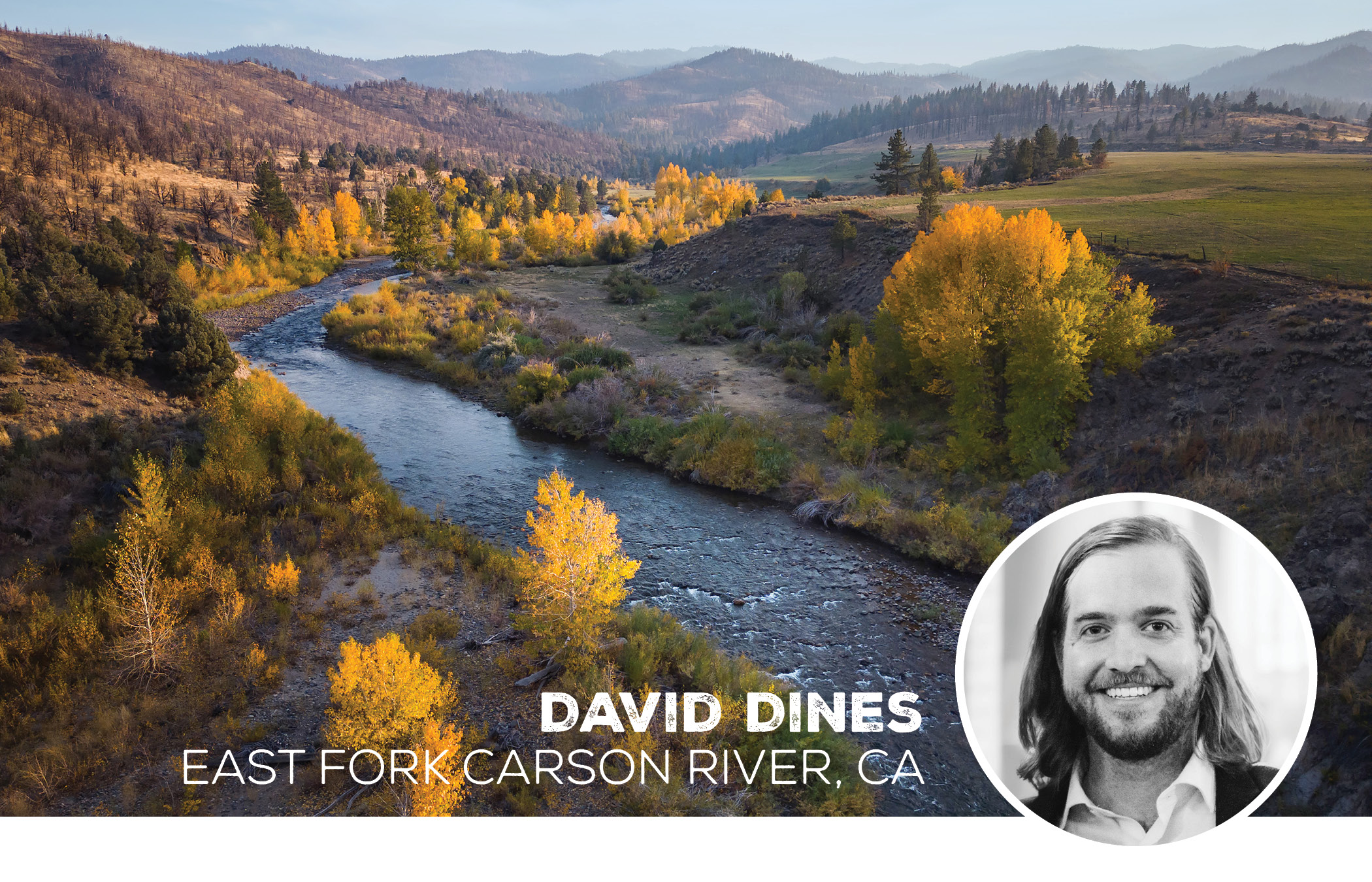

What was your favorite part about shooting the East Fork Carson River?

What was your favorite part about shooting the East Fork Carson River?

When you show up to a property with a lockbox code and carte blanche to fish and photograph your favorite people, that's as good as weekends get. Tough to pick a favorite moment, but on our last afternoon—after covering a lot of miles and getting a lot of great images—I caught a nice rainbow on my first cast with the unfailing guidance of Jon Ng. That particular hole produced a lot of great fish and photos, but up to that point I'd been on the other side of the lens. Jon pointed me across the river where I ungracefully landed my largest fish of the weekend, wrapping up a great shoot.

What challenges did you have during the shoot?

The shoot was great, no notes. The drive home was a reminder that rain and speed don't mix, and great photos mean squat if you don't get back in one piece. Jon and I were caravanning over the pass, and a tail-gaiting Tesla kept weaving through traffic. Eventually he overtook Jon (who conveniently has a dash cam), lost control, and smashed into the median at 70 miles an hour. He totaled his car and managed to roll to the shoulder, and after making sure he was ok, I called ahead to Jonny who was about one-car-length from having a real bad time. Thankfully everyone was fine, and the footage was pure schadenfreude. We've watched the video many, many times.

What are your top tips for photographing rivers?

In reality, 90 percent of my best river photos come from the first or last hour of the day. If it's bright and the sun is harsh, there's nothing wrong with putting the camera down and picking up a rod or taking in the surroundings. Have fun, scout your area, and go with good anglers. I've been saved many times because my friends are great fishermen, much better than me, and can turn average days into spectacular photoshoots.

See more of David's work: David is the founder of Dines & Co. and creative director for California Fly Fisher. He's on Instagram at @dines.co.

.jpg) What was your favorite part about shooting the Middle Fork Salmon Headwaters?

What was your favorite part about shooting the Middle Fork Salmon Headwaters?

My favorite part was probably in the very last light having a herd of elk start running alongside my car when I was just about ready to pack it in for the day. They came out of nowhere and were in a large herd of more than 20 animals. I did pop off a few exposures as they moved across the Cape Horn Ranch property. It was kind of ethereal as they were mostly shapes and silhouettes to my eye. The ability of high ISO settings on the new digital cameras doesn’t really show how close to “really dark” it was at the time of the elk encounter!

What challenges did you have during the shoot?

I had a super helpful river guide named Sita, from White Cloud Rafting, who agreed to help me with some fly fishing photographs in the late afternoon/evening. We were all suited up in our waders and gear, on a really nice stretch of the Salmon River at Cape Horn, when all of a sudden a big black wall of smoke started developing to our west in the direction of Lowman. This gave us about 15 or 20 minutes to get our photographs and then get out of the area. The fire ended up being quite significant, closing the roads west of Stanley for quite some time. (Cape Horn didn’t incur any damage from this forest fire.)

What are your top tips for photographing rivers?

Rivers have many moods, so I would say there are no rules. Specular highlights off the water’s surface are very beautiful, and the colors reflected in the water's surface can be very stunning. A moving river's flow might be a great opportunity for a slow shutter speed with a blurred motion effect. A still section of water could lend itself to some extra awesome reflections of the surrounding landscape.

Wildlife and birds nesting in the area can add an interesting element to the scene as well. Early and late light are great times to explore different moods as well as the slow shutter speed approach by using a tripod. Mid-day (usually a No No), could be an excellent time to try the possibilities of using a polarizer on the water’s surface. Exploration and experimentation will always lead to new insights. Changing weather patterns can really add a dynamic element to any landscape photograph. The high angle is usually very dramatic for an overall aspect of a river (maybe a drone or hike up a hill if possible). I would say also that just staying put along the river’s bank will help you develop a better connection with the subject. Patience!

See more of Kirk's work: kirkanderson.com/index

.jpg) What was your favorite part about shooting the John Day River?

What was your favorite part about shooting the John Day River?

There is something magical about exploring along a wild river in early morning, watching the sunlight touch the clouds then the higher hilltops and finally touch the water as it ripples along. It is usually quiet and still, only a few bird songs, and the gentle murmuring of the river for background sound—a good time for feeling alive and included as a small piece of an outdoor scene.

For Pat and I, this quiet and energizing time was enhanced along the John Day by being in the “open” country east of the Cascade mountains. Having spent much of our outdoor time on the West slope or coastal side of this mountain range it was invigorating to walk in the expansiveness of the setting along the John Day.

We love working with Western Rivers on photoshoots as their mission and values line up well with our own. We appreciate the opportunity to be a part of making a difference.

What challenges did you have during the shoot?

One of the biggest challenges in all outdoor shoots is to know where to be for the morning or evening light. It often comes early and goes fast. We were grateful WRC included extra days in this shoot to give us time to hike the vast river basin to find the best views for this project.

The afternoon or evening scouting trip also helped us know how much time was needed to hike back to this location at least a few minutes before “shooting time” the next morning, making sure we got up early enough to beat the sunrise.

What are your top tips for photographing rivers?

A good zoom lens is our preference for river images—probably 75 to 80 percent of our river images are taken with a 24-120 mm or equivalent zoom lens. It allows the photographer to form the images easily and quickly. In open terrain like the John Day, we wanted to show the river in its setting by including the more wide-angle views a smaller lens provides. A larger telephoto lens will tend to isolate the river and exclude the habitat through which the river flows, which often is so essential to the river’s story.

A blue sky day is helpful if you hope for a lovely blue river.

We probably don’t need to state the importance of good hiking boots and a walking stick or monopod—which if nothing else—are great for scaring the potential snake off the trail.

See more of Tom and Pat's work: leesonphoto.com

What was your favorite part about shooting the North Umpqua River?

What was your favorite part about shooting the North Umpqua River?

The North Umpqua is still one of my favorite rivers. It has a sense of mystery to it, with endless corners to explore and a lot of history layered into it. On that trip, I met Lee Spencer, who used to watch over the steelhead on Steamboat Creek. We ended up running up and down the river as he pointed out fish that I would have completely overlooked. Spending time with him and hearing his stories while watching the river in that way made the whole experience pretty unforgettable.

What challenges did you have during the shoot?

Falling in with a full bag of camera gear is always in the back of my mind. I’ve drowned a lot of cameras over the years but that’s part of the deal when working on rivers. Some places are easy to move around, others feel like walking on greased bowling balls in waders. The other challenge is light. When it’s good, I want to be in three different spots at once, so it’s always a scramble to make choices quickly.

What are your top tips for photographing rivers?

I usually start well before sunrise because those first few hours of light are the most dynamic. Fog can roll in, wildlife is active, and the river changes by the minute. I typically carry two cameras—one set up on a tripod for landscapes and another slung over my shoulder with a telephoto for wildlife. It feels clunky, but being ready for both makes the difference when things unfold fast.

See more of Tyler's work: TylerRoemer.com and on Instagram at @TylerRoemer.

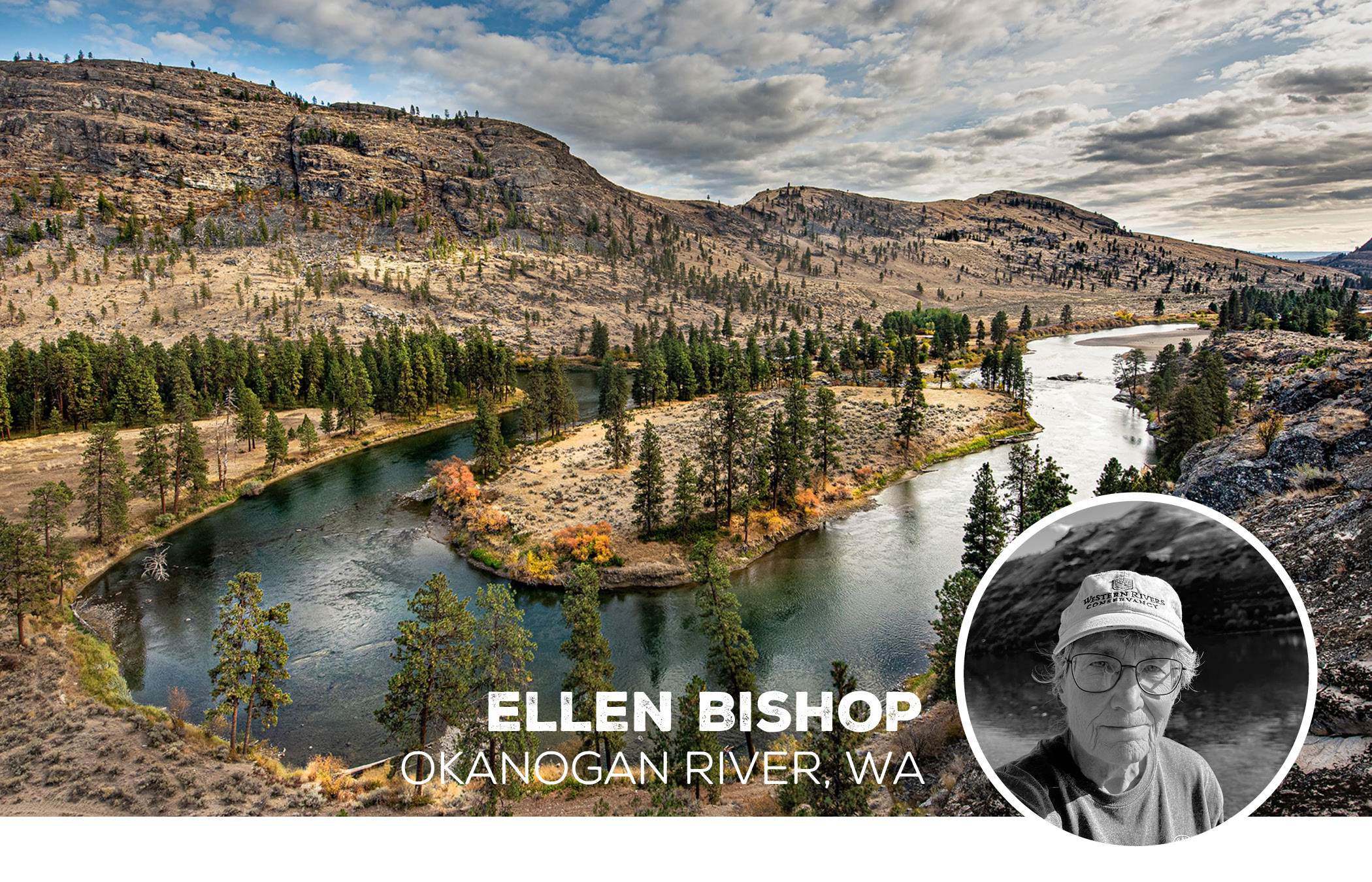

What was your favorite part about shooting the Okanogan River?

What was your favorite part about shooting the Okanogan River?

Being part of Western Rivers Conservancy's support of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation’s work restoring sockeye and other salmon and steelhead runs on the Okanogan River. The Okanagan River sockeye population is one of only two remaining populations of sockeye salmon in the international Columbia River Basin. I am deeply concerned about the loss of salmonids, especially sockeye—a fish that requires river-connected headwater lakes for spawning and rearing, and was once prolific—but now extinct in their home area of Wallowa Lake, Oregon.

What challenges did you have during the shoot?

First, photography is all about capturing light. For much of my time at McLoughlin Falls, the sun played hide-and-seek through the clouds, which began to crowd the sky as the day progressed. Shooting images later in the day meant finding the right viewpoint, and then waiting for the sun to paint the landscape with somewhat limited and delicate light. Sunset did not bring the radiant reds and oranges I'd hoped for. But there was sufficient good light to capture all that I needed to.

Secondly, finding great viewpoints along the river in the southern portion of the property required underbrush navigation. But the game trails I mostly followed revealed signs/tracks of bear, deer, elk and possibly a weasel, an encounter with a bull snake, plus wild turkey feathers and other hints of unseen wild inhabitants and provided useable views of the river. So, this search was partly a challenge, but also a delight.

What are your top tips for photographing rivers?

Rivers are more than just pretty watercourses. They are vital parts of living systems, active sculptors of landscapes, and glimpses into time. Each is unique. As Robert McFarlane notes in Is a River Alive, "Each river is differently spirited and differently tongued—and so must be differently honored.”

As a river photographer, I am making a portrait of an individual (the river) and of its family (the river's landscape, plants, animals, and geology.) That includes photographs that feature the river and its flow at different scales, in different lighting, and different angles as well as what might be considered "family portraits" of the landscape including plants, animals, and geology.

To better depict the power of water, I shot with a high shutter speed to capture the water's vigor, rather than using a very slow shutter speed to make the water look tame and silky. I included closeups of native milkweeds casting cottony seeds into the air, native grasses bowing to the wind, and many other components of the riverine ecosystem. Here, and in all my photography, I try to remember the great advice I got from my first photo editor, Phil Bullock, when I was a cub photojournalist at The Observer in La Grande, Oregon: "Get close. Then get closer."

My top tip for photographing rivers is that a river is more than water. It is a living ecosystem that spans time and distance. Take as much time as possible to get to know the river, or the segment you are depicting.

As you explore the area you'll be shooting, consider the direction the light will be coming from when planning your shoot. 15-plus minutes before dawn into early morning, and as much as 15-plus minutes past sunset are the best times for landscape images. But these times may not work if you are shooting a riverine canyon. You can also plan ahead of time using Google Earth. Apps such as Photographers Ephemeris and/or PhotoPills, which will show the angle of the sun, times of sunrise and sunset, and more at any location at any time and on any date.

Your first images might capture the nature of the river's flow, for that's what defines a river for most of us. Is it uniformly fast, with lots of rapids? Or uniformly genteel? Or both? Is there a transition you can capture? Do you want the river to look turbulent? Smooth and silky? (Bring along a tripod and a 6X or 10X neutral density filter if you choose smooth.)

Who else lives here? Who else does this river support? Are there goose, rail, or deer tracks in the sand? Evidence of bank beaver gnawing trees? Birds nearby? (Telephoto capacity is handy here.) Important plants? Cattails in abandoned meanders? Can you include the river in these images? (Hello, wide-angle lens...I use a 16mm or 20mm for these.) Closeups of plants in action can be fun. I use a Sony 70-200mm f4 -macro lens for these.

Neither Lightroom nor Photoshop can faithfully replace or duplicate natural light.

Don't forget the dictums of composition that include use of leading lines, details that lead the eye through the image and back again, and sky, not just river.

Most of all, observe this living system with all your senses and be very glad that you are its portrait photographer.

See more of Ellen's work: ellenmorrisbishop.com